The Effects of Employee Recognition on Worker Health

訂閱時事通訊

Recognize Research Team investigated if employee health is affected by a sense of appreciation. Dan Pink in the book Drive showed us how autonomy, mastery, and purpose drive employee motivation. To have a sense of purpose is partly due to others reminding you have a purpose, or recognition for your work. If you receive less recognition, will that also affect your mental or physical health? We looked into it after surveying the general population.

“People want to be respected and valued for their contribution. Everyone feels the need to be recognized as an individual or member of a group and to feel a sense of achievement for work well done or even for a valiant effort.”(Harrison, 2019)

Abstract

Employee recognition has been established as an important aspect of having an effective workforce. A good amount of research has been done on how recognition is related to important factors such as productivity and job satisfaction. In order to develop new insights and test the results of previous studies, Recognize, Inc. conducted a research study on whether employee’s satisfaction of their recognition is related to both physical health (measured by sick days) and mental health. A sample was run on about 400 Mechanical Turk participants across America and found that while employee recognition had no relationship with sick days, it did have a slight relationship with mental health. This research points to the growing evidence that recognition is an important part of employee well-being.

Introduction

Improving employee engagement is truly symbiotic. Employees benefit from having a good experience at work, and research has clearly established that employers benefit from greater productivity and performance (Markos & Sridevi, 2010). One component of employee engagement is employee recognition. Like many other conceptual terms (including employee engagement itself), employee recognition escapes an ultimate definition on which everyone agrees (Brun & Nugas, 2008). At Recognize, one way we have framed employee recognition is as follows:

Employee recognition is the act of showing staff appreciation for the good work they do. It can be a formal process, such as in a communication tool, or an informal process, a side conversation between a manager and an employee. Employee recognition can come in many forms and events, including employee service anniversaries or employee of the month.

Although it sounds intuitive that employee recognition would lead to positive outcomes in the workplace, it is far more than just a good idea. A multitude of studies and academic papers on the subject have been supporting the value of employee recognition with data. Some of the findings include:

What is Healthcare Burnout?

- That employee recognition results in greater job satisfaction (Tessema, Ready, & Embaye, 2013)

- It leads to an increase in productivity (Tessema et al., 2013)

- It “promotes positive psychological functioning and its absence worsens it”. (Merino & Privado, 2015)

- Most employees feel the need to be recognized, but many are dissatisfied with the recognition they receive (Harrison, 2019; Luthans, 2000)

With all this research in the background, Recognize, Inc. decided to conduct an additional study on employee recognition to see how the results compared to previous findings and if new ground could be uncovered.

This study concentrated on the relationship between employee recognition and health (both physical and mental health). The population was originally employees worldwide in the banking sector, but was later modified to employees throughout the United States due to limitations obtaining participants.

The variables were defined in the following way. Physical health was measured by the number of sick days that an employee had taken in the past 6 months. This construct, while not a perfect indicator of a person’s general health, was an appropriate and practical measure of how an employee’s health impacts the company in which he or she works. Mental health was measured using an established mental health questionnaire, which is explained in more detail in the next section. For this experiment, employee recognition was measured as a construct of how much employees felt appreciated for the work that they do. Several survey items were used to measure this variable.

The relationship between number of sick days and the mental health construct were accessed separately – that is, with two different correlation and regression models. It was hypothesized that there would be found a significant relationship between employee recognition and both sick days and mental health.

Survey Method

After constructing the research question and conducting the literature review, a survey was created to gather the data for the study. The survey accessed more aspects of the variables and research topic than were required, to provide a fuller understanding and provide data that could be used in future research endeavors.

As mentioned in the previous section, the population of interest was employees within the US. While the main goal had been to analyze employees from the banking industry internationally, it was difficult to gather as many people for the experiment (even through Mechanical Turk), and therefore the research question was shifted to match the time and budget.

The survey accessing the general employee population in the US was thus released via Mechanical Turk. Several questions in the beginning of the survey were a consent to participate and a request for the participant’s Mechanical Turk ID to ensure that all surveys were conducted by legitimate participants (and to later identify and remove duplicates). All questions were marked required, although the option “Prefer not to answer” was provided on all questions except for those that were free-response. Participants were briefly told that they were taking a survey on health and employee recognition. Details were intentionally left out to keep participants engaged by using brief text and to avoid potentially influencing the participants’ responses.

The three main variables of interest (the independent variables sick days and mental health, and dependent variable employee recognition) were measured in different ways throughout the survey. Sick days was the simplest, captured by a simple question, “In the past 6 months, how many sick days did you take from work?”, and followed by a free-response that accepted only numerical responses.

Mental health was constructed with an inventory based off an established mental health questionnaire, the PHQ-9 (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). The last question from the PHQ-9 on suicidal ideation was omitted due to its very sensitive nature and it being beyond the scope of the mental health aspects that needed to be examined. Therefore, the research survey included 8 out of 9 questions on the original PHQ-9. Questions assessed how often participants had been undergoing certain phenomenon (such as feeling tired or down), on a scale from 0) Never to 3) Nearly every day. The full list of questions can be found in the original survey, which is linked in the Appendix.

The construct of employee recognition was also accessed through a series of questions. In this case, three questions were asked about the employee’s experience with feeling appreciated in the workplace, which consisted of statements in which participants needed to respond on a Likert Scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree, within the timeframe of the past 6 months.

- "I have felt like my company recognizes my accomplishments."

- "I have been satisfied with the employee recognition I receive."

- "I believe I have been adequately recognized at my company."

Both the mental health and employee recognition inventories used in the survey were measured for reliability / internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha for both tests were highly reliable, over a value of 0.9. The mental health inventory was accessed on the 365 participants who responded to all the questions and had an alpha of 0.91 for 8 items. The employee recognition inventory, accessed on 369 participants, had an alpha of 0.97 for 3 items.

Both the original survey in the banking industry and the one for the general US population (which was actually used for the analysis) were created using TypeForm and released using Mechanical Turk. Participants were compensated for their time. The survey originally had 401 responses. Of these, 5 duplicates were found (entries that had the same Mechanical Turk ID). These were removed, leaving a sample size of 396.

In addition, the survey checked several conditions to control for confounding variables. Participants needed to confirm that they had been in their current job role for the past 6 months, and to answer all questions within that timeframe. Additionally, the survey asked several demographic questions, one of which required the level of the participants’ job position. The following options were given:

- Entry level

- Intermediate or senior level

- Management / supervisory role

- Upper management

- Contract

- Part time / Intern

- Self employed

- Prefer not to answer

Those who replied with “Contract,” “Part time / Intern”, or “Self employed” were removed from the analysis, leaving a sample of 371. In addition, missing values or those who selected “Prefer not to answer” were also removed. After this, the sample was 369.

Results

After data was collected, two separate correlation and regression models were run on the variables of interest, sick days and mental health. Variables were treated as ratio / interval for the purpose of this experiment.

The independent variable of number of sick days was simply a ratio variable. The other two variables, mental health and employee recognition, were both measured using several Likert-type items. Mental health was accessed across 8 questions using a 4-point scale with the values of “Not at all”, “Several days”, “More than half the days”, and “Nearly every day.” Employee recognition was accessed across 3 questions using a 5- point scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. All of these Likert-type questions were averaged into one Likert Scale mean value (for both mental health and employee recognition) that was used in the analysis.

There is much discussion in academia on the topic of whether Likert-type items and Likert scales can be considered as interval data or if they are only accurate when constructed as ordinal data, with plenty of support on either side – that being said, since quite a bit of the research has argued that Likert scales can be considered interval data, this recommendation was followed for this experiment (Joshi, Kale, Chandel, & Pal, 2015). One limitation of this study is that one of the Likert scales (mental health) was composed of 4 Likert-type items, rather than the 5-7 items that are recommended to consider the data interval (Brown, 2011). This is further discussed in the “Discussions, Limitations, & Future Guidance” section of this paper.

Physical Health

The data was first analyzed for any missing values in the number of sick days. There was none; therefore, the analysis was run with all the 369 people from the dataset.

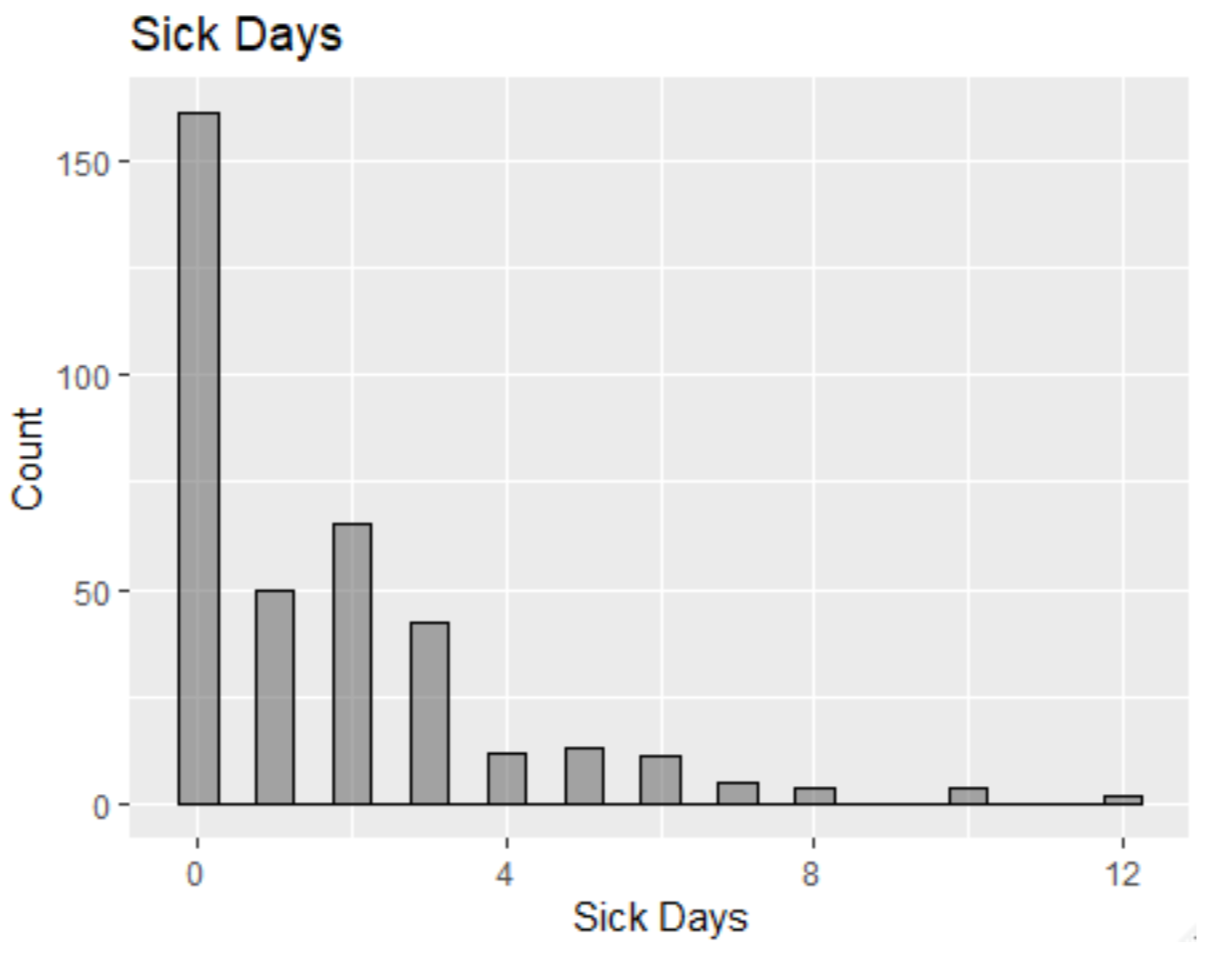

A visualization of the number of sick days quickly revealed that the data was highly positively skewed. The data had a median of 1 and IQR of 2. In other words, the vast majority of employees did not take many sick days, with the center point being only 1 sick day off from work in the past 6 months.

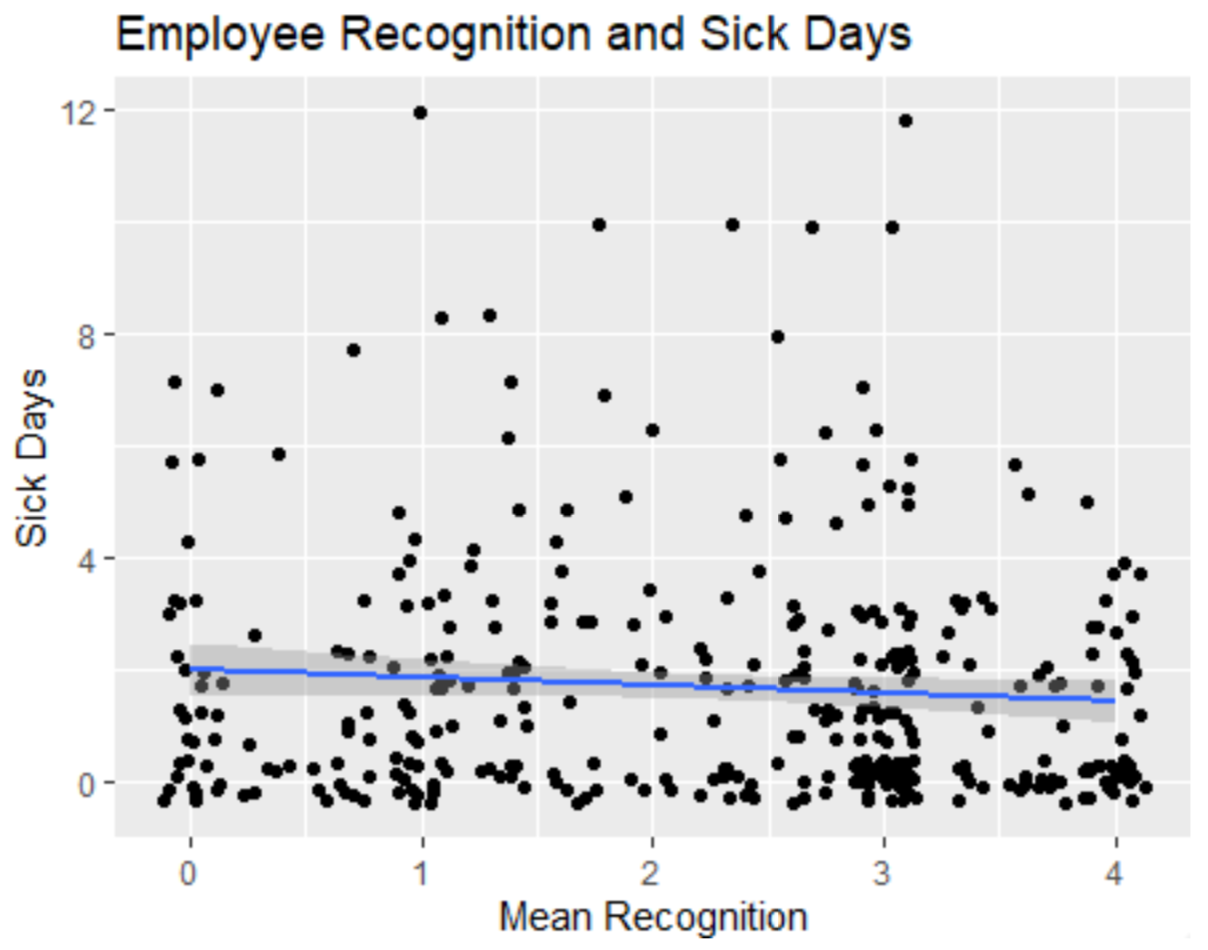

Since the data for sick days was positively skewed, a Kendall’s Tau correlation and Kendall–Theil nonparametric linear regression were chosen for the analyses. This non-parametric linear regression model is robust to outliers, so outliers were not removed. The Kendall’s Tau value was -0.0722 (p > 0.05), which is not indicative of a significant relationship. The regression model yielded a nonexistent slope of less than 0.000 (p < 0.05). Although the p-value was less than 0.05, this was most likely because of the large sample size, for there was truly no meaningful relationship.

The following jitter plot helps illustrate the results (a jitter plot is similar to a scatterplot, but spaces out points when many of them have the same value. Using a scatterplot, the points would be stacked on top of each other).

Employee Recognition Affects Mental Health

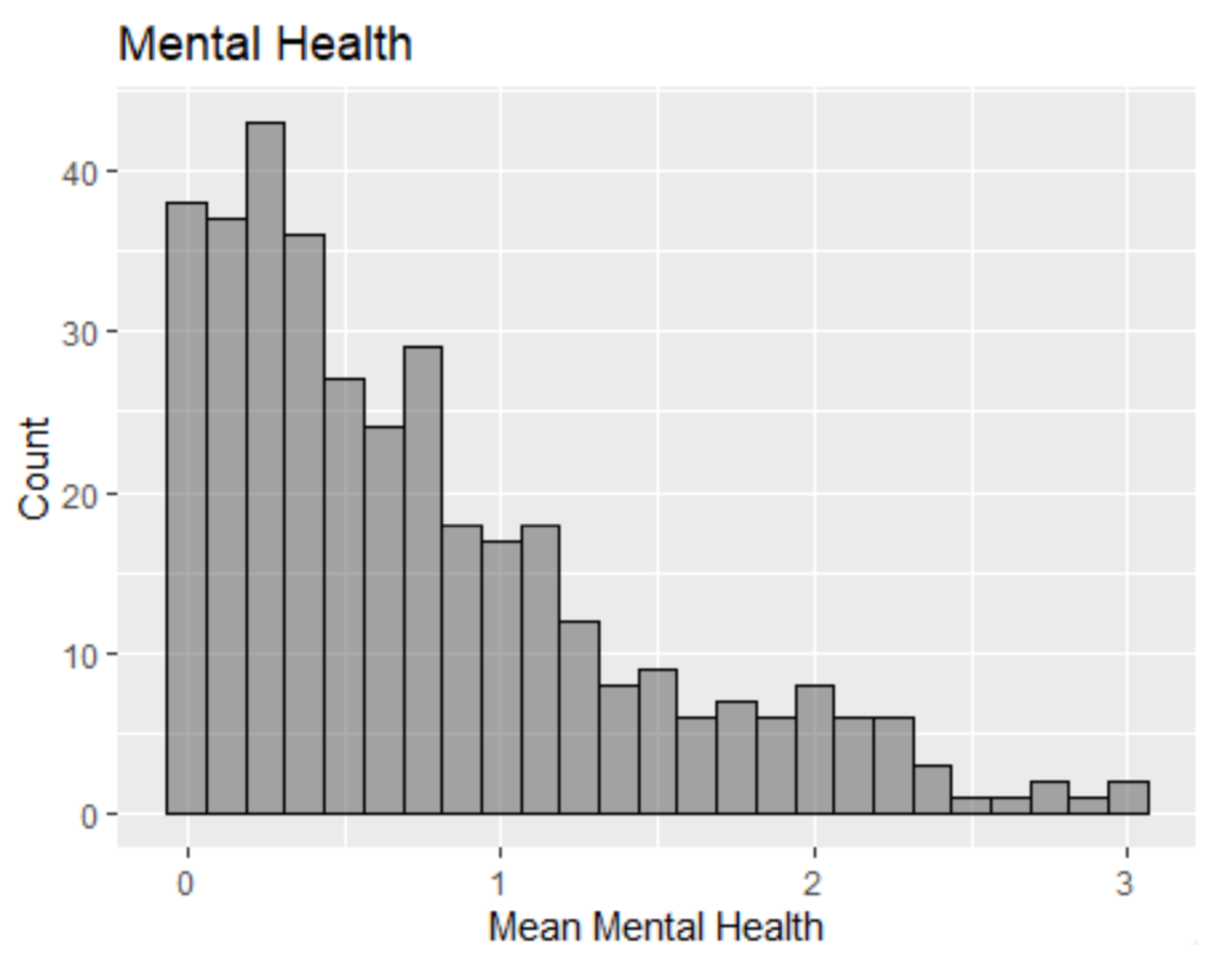

The other variable of interest was mental health. Upon examining the dataset, 4 missing values were found for the responses on the mental health questions. Responses with missing values were removed, leaving a sample size of 365.

The data for mental health was also positively skewed, though not as severely as the distribution of number of sick days. On a scale from 0 – 3, the data had a median of 0.625 and IQR of 0.875. Since lower mental health scores corresponded to better overall mental health, these results indicated that the participants were high in mental health.

Note: Lower scores on the mental health construct indicate better mental health

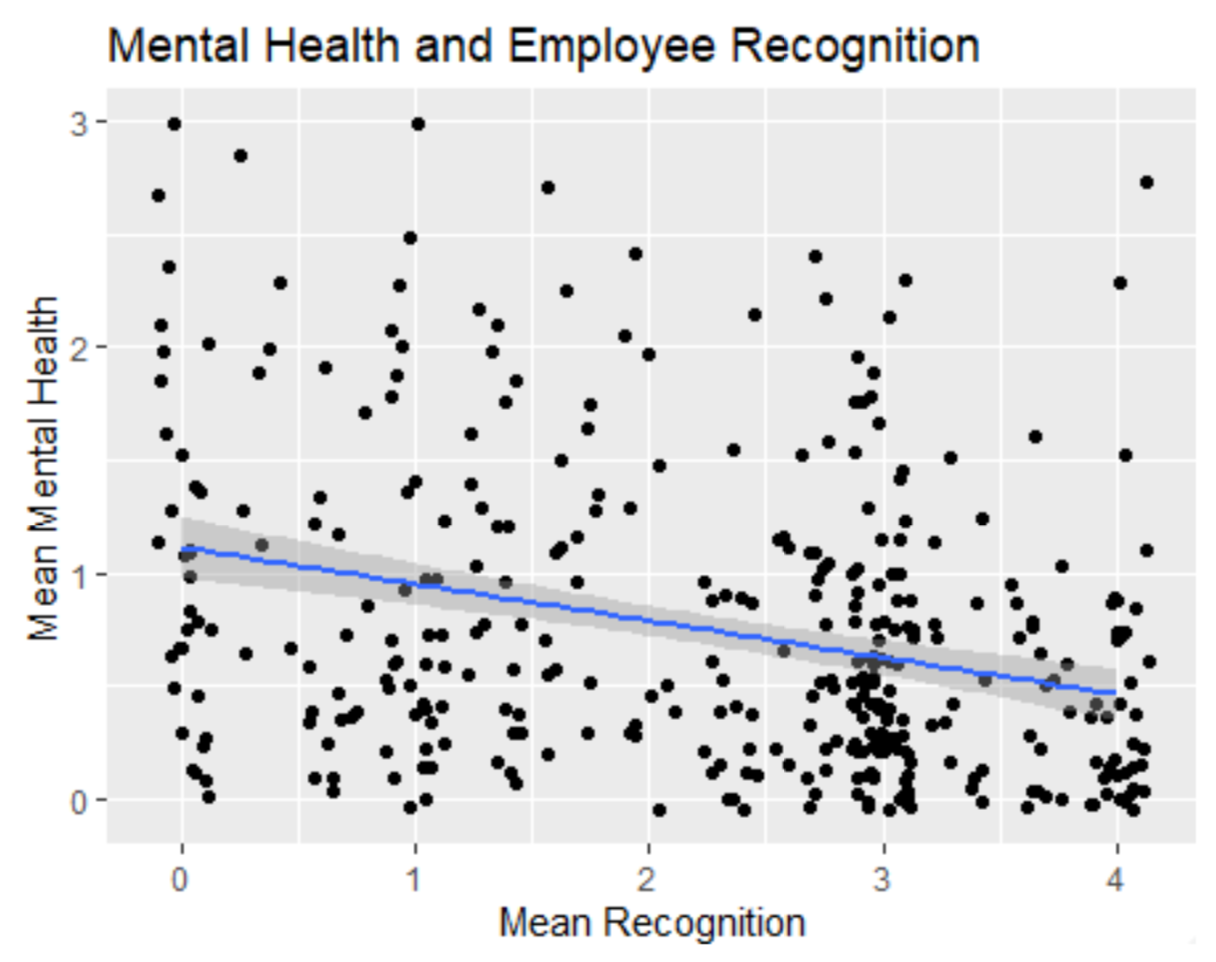

Similar to the analysis on sick days, a Kendall’s Tau correlation and Kendall– Theil non-parametric linear regression were run on the positively skewed data. The Kendall’s Tau value was -0.2190 (p < 0.05), indicating a mild, significant relationship. The regression model showed a slope of -0.1500 (p < 0.05), which also indicated a mild and significant relationship.

The following jitter plot visualizes the results. The concentration of points in the bottom right corner shows that there was a good portion of participants who had both high satisfaction with the employee recognition they received and good mental health (indicated by a low score on the mental health inventory).

Note: Lower scores on the mental health construct indicate better mental health

Discussions, Limitations, & Future Guidance

The analysis demonstrated that employee recognition had no relationship with sick days but did have a slight relationship with mental health.

Interestingly, previous research did find a relationship between employee recognition and absenteeism (Nelson, 2015). It is possible that there is a correlation that was just not found in this particular study. Before the analysis, it was hypothesized that sick days may not have a clear relationship with employee recognition, seeing that there are many other factors that may impact sick days as well.

The findings on mental health, taken with studies from the past, indicate that it is possible that recognition impacts mental health (more research would be necessary to draw this conclusion). Although the relationship between the two variables in this study was slight, it was still noteworthy. Practical significance of an experiment is determined by the importance of the construct it is measuring – small changes can be truly meaningful in important variables. Research has firmly established employee mental health as a vital factor of the workplace, indicating that any means to improve it may be well worth the investment (Goetzel, Ozminkowski, Sederer, & Mark, 2002).

It has been exciting to see the research done in this area and it will be exciting to see what is to come. This study did have several limitations that should be conceded, and may be worth considering for potential future projects. One is that, as mentioned, one of the Likert Scale constructs was developed from Likert-type items with 4 answer choices (less than the recommended number of responses for constructing interval variables from Likert Scale data). It would be interesting to see a similar study run using a different inventory for mental health, or perhaps one that analyzed Likert Scale data as ordinal as well.

In addition, the study was conducted using Mechanical Turk over the general population. Additional studies that narrow in on a certain part of the population, or use a different sampling method, may also be useful in replicating results.

Overall, the study revealed interesting findings that help build the increasing case that employee recognition may be a valuable component of something that all employees need to be successful: good mental health.

References

104 Top Recognition Ideas. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://recognizeapp.com/top-employee-recognition-ideas

Brown, J. D. (2011). Likert items and scales of measurement? SHIKEN: JALT Testing & Evaluation SIG Newsletter, 15(1) 10-14. Retrived from http://hosted.jalt.org/test/bro_34.htm

Brun, J. P., & Dugas, N. (2008). An analysis of employee recognition: Perspectives on human resources practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(4), 716-730. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190801953723

Goetzel, R. Z., Ozminkowski, R. J., Sederer, L. I., & Mark, T. L. (2002). The business case for quality mental health services: why employers should care about the mental health and well-being of their employees. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 44(4), 320-330. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-200204000-00012

Harrison, Kim (2019). Why employee recognition is so important – and how you can start doing it. Retrieved from https://cuttingedgepr.com/free-articles/employee- recognition-important/

Joshi, A., Kale, S., Chandel, S., & Pal, D. K. (2015). Likert scale: Explored and explained. British Journal of Applied Science & Technology, 7(4), 396. https://doi.org/10.9734/bjast/2015/14975

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ‐9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606-613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Luthans, K. (2000). Recognition: A powerful, but often overlooked, leadership tool to improve employee performance. Journal of Leadership Studies, 7(1), 31-39. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F107179190000700104

Markos, S., & Sridevi, M. S. (2010). Employee engagement: The key to improving performance. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(12), 89-96. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v5n12p89

Merino, M. D., & Privado, J. (2015). Does employee recognition affect positive psychological functioning and well-being?. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 18, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2015.67

Nelson, B. (2012). 1501 ways to reward employees. New York, NY: Workman Publishing.

Tessema, M. T., Ready, K. J., & Embaye, A. B. (2013). The effects of employee recognition, pay, and benefits on job satisfaction: cross country evidence. Journal of Business and Economics, 4(1), 1-12. Retrieved from http://www.academicstar.us/journalsshow.asp?ArtID=371

See how Recognize helps companies promote company values and a culture of appreciation.

與我們見面